Of NOBA’s 125 churches and missions, 43 are African-American, Spanish speaking, or Asian congregations. We are the most ethically diverse association in the state. The SBC is beginning to reflect the diversity of our faith community in New Orleans, with about 10,000 “ethnic” congregations among the 46,124 churches of the SBC.

We celebrate the diversity of our faith community because we know that we are beginning to reflect the saints in glory whom God will call from every nation, tribe and tongue. But our country, city, and denomination were not always inclusive. During my childhood, segregation was deeply imbedded in our city and denomination. My childhood memories include “White” and “Colored” water fountains in public buildings, “colored” seating on busses and street cars, and segregated swimming pools, theaters, amusement parks, and public schools.

Separate was never equal; it was mean and ugly. Segregation was based on ignorance and fear, and it was maintained by political power. All that was wrong with segregation was compounded when it was practiced in churches, because in Christ there is no division between people. Instead, we were all one body with Him as our head.

Over the course of my life, we have come a long way toward racial reconciliation. We stand in honor of those who took giant steps in helping us bridge the divide that once separated us. One such person was the child Ruby Bridges.

In the November 14th issue of The Crescent City Times, the school newspaper for Crescent City Christian School, Principal Bob Brian published the following editorial. It is reprinted here with his permission:

The Heroes Among Us

by Robert Brian

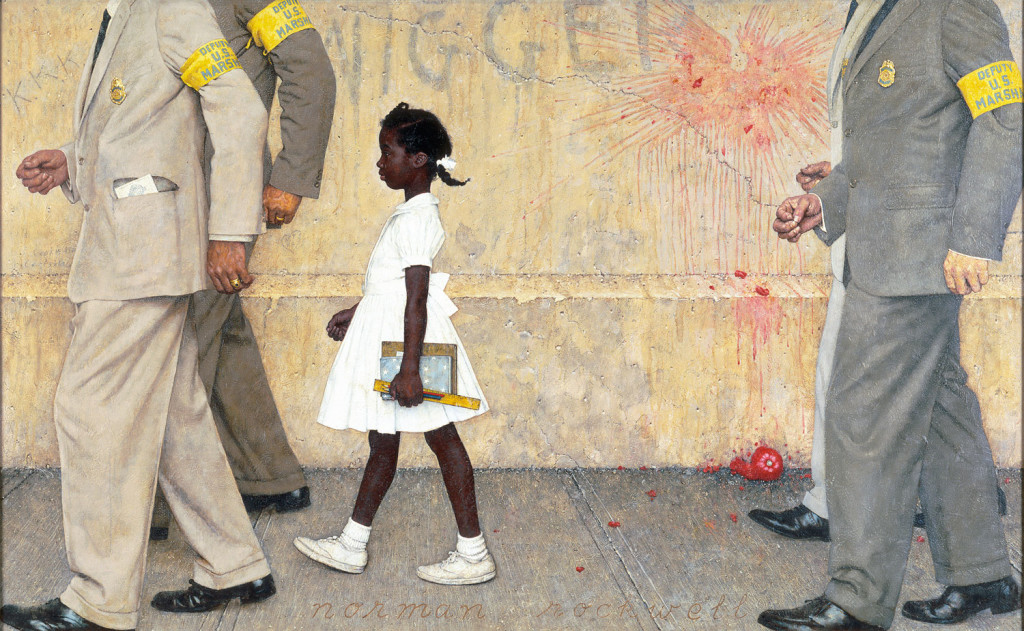

The Norman Rockwell illustration accompanying this editorial was published under the title “The Trouble We All Live With” on the January 1964 cover of Look magazine and since has become an iconic expression of the racial and political tension that typified the heroic struggle to desegregate all-white public schools in the South following the Supreme Court’s mandate in Brown vs. Board of Education (1954). Rockwell’s now famous Look cover was a moving reminder in the Civil Rights era of a scene enacted on the national stage right here in New Orleans on Monday morning, November 14th, 1960, fifty-four years ago today.

The little girl in the picture is Ruby Bridges, who walked alone that day, flanked by federal marshals, into the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in the Upper Ninth Ward. The same day three other first-grade girls, better known to posterity as “The McDonogh Three,” desegregated McDonogh No. 19 (now Louis Armstrong) in the Lower Nine. Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost, and Gail Etienne — along with Ruby — all still reside as adults in New Orleans.

The November 19th issue of The Louisiana Weekly, the “voice of the African-American community” in Louisiana, reported that week that the girls’ courageous steps into history had occurred “without violence, as hundreds of New Orleans police officers encircled both Orleans Parish schools” and brought an “end [to] segregation, as crowds outside the schools sounded cheers, jeers and some boos.”

The attention garnered by Ruby’s solitary walk and a year spent in the classroom alone with her teacher — not to mention Steinbeck’s mention of her in Travels With Charley, Rockwell’s illustration, and the interest of Harvard child psychologist Robert Coles — all combined to transform Ruby into a civil rights icon, while with the passage of time, Leona, Tessie, and Gail more often than not are relegated to the parentheses of history for an achievement no less remarkable. The truth is that all four of these ladies and others after them who made similar sacrifices for our benefit walk today as heroes among us and deserve not only our remembrance, but our respect and admiration as well.

For a poignant portrayal of what that kind of respect looks like we have only to re-thumb the dog-eared pages of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel To Kill A Mockingbird, published the same year. Do you remember the scene after the trial was over? In a rural courthouse on the central square of the fictional Maycomb, Alabama, Tom Robinson, a black man, has just been wrongly convicted of a heinous crime against Mayella Ewell, one of the town’s white women, and Atticus Finch, his court-appointed white lawyer, has packed up his briefcase and turned from the well of the court toward the rear doors. With slow and burdened steps he starts down the aisle, the weight of the world pressing down upon him.

No seat on the main floor of the courtroom is available, and in the segregated South the black community in town has been relegated to the balcony for the trial’s duration. Seated with them, by special invitation from Reverend Sykes, is Scout Finch, Atticus’s headstrong six-year-old daughter. As Atticus continues depleted down the aisle, suddenly all the folks in the balcony stand — all except Scout, who can’t figure out what’s going on. When the old preacher nudges her and tells her to stand with them, she asks why. Using Scout’s full name as adults sometimes do for emphasis, Reverend Sykes says, “Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your father’s passing.”

As we mark the anniversary of this important event in history we should not fail to recognize that all of us — black and white alike — are the beneficiaries of the courageous steps on this day in 1960 of Ruby and her peers as they crossed the lines of desegregation for the first time. So, Crescent City, stand up! The heroes among us are passing.